At the risk of turning my Substack into a newsletter about BP and Elliott, I obviously have to comment on the combination of the FT piece yesterday and related filing showing Elliott with a large derivative position in the company.

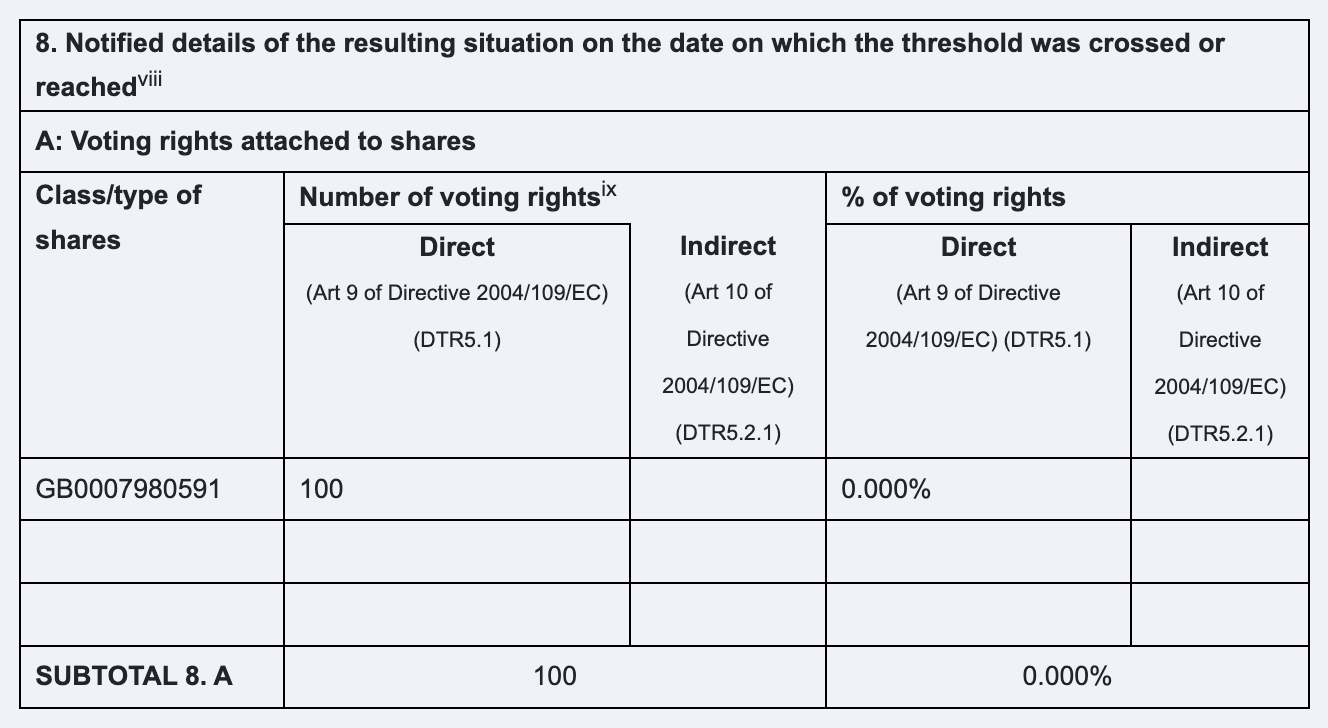

Looking at the TR-1 filing first, it shows that Elliott does not hold 5% of BP’s shares. In fact it holds (chuckle) 100 BP shares.

Its primary exposure to BP is through derivatives - equity swaps in this case. And because Elliot has now acquired voting rights it has triggered a TR-1.

So this is consistent with what we saw last week. My hunch was that Elliott had previously built a large derivative position but initially not acquired voting rights. That in turn meant a counterparty somewhere was holding the underlying equity which went un-voted last week, resulting in reduced turnout at the AGM. Now it has acquired the voting rights, hence the TR-1.

As a side point, according to this filing, Elliott acquired voting rights last week on Wednesday 16th April - the day before the AGM. I’m guessing that would have made it impossible to vote at the meeting in any case, though organisations with deep pockets can often get what they want. But more generally it likely indicates that the AGM was not of particular importance to Elliott. As I wrote last week, media reports stated they wanted the BP chair out. So that fact that a separate group of investors, with radically different motivations, also gave Helge Lund a boot was likely a small unexpected bonus, but largely irrelevant.

As I also wrote, the fact - now confirmed - that Elliott appeared to have held its position through the AGM suggested their interest in the company was not over. I can’t believe a firm like Elliott would be sloppy enough to acquire voting rights too late in the day to be able to use them. So the acquisition of these rights can be read as a signal of further pressure. Crossing the 5% threshold in terms of voting rights enables them to requisition resolutions, for example.

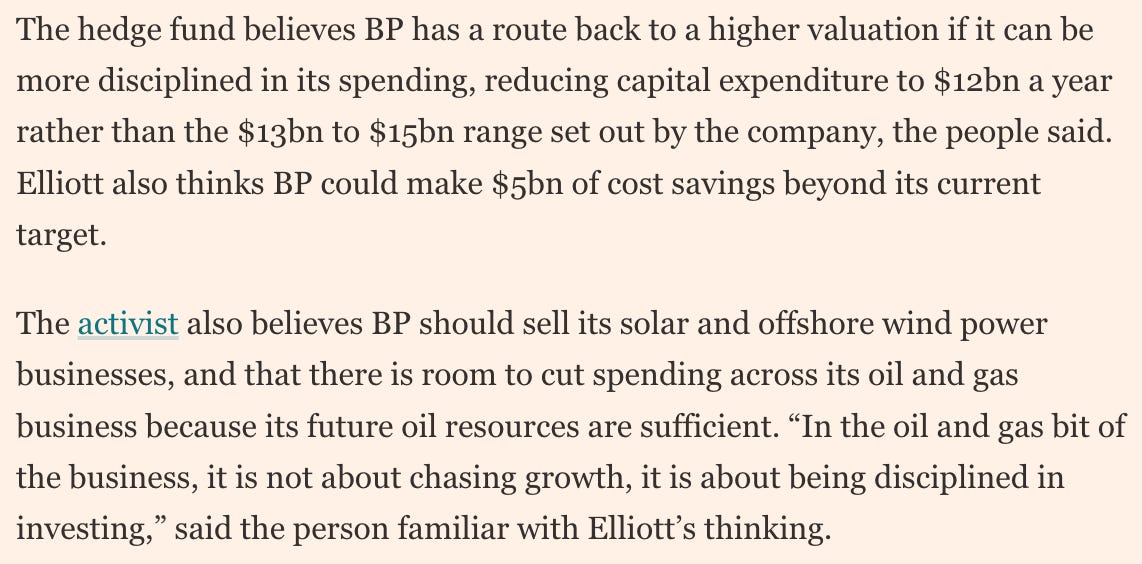

Elliott’s desire for further change at BP is confirmed by the FT piece.

I’ve been following this type of activity at a distance for several years, because the interests of Elliott have not always been shown to be perfectly aligned with those of other stakeholders. I’m also interested in where it fits into ‘stewardship’.

What we are witnessing at BP is the contest between the more high-minded version, with a strong ESG focus, and the more old-school purely financially-motivated activist investor model. These are distinct types of investor activity that have become conflated, which can lead to much confusion. The Guardian’s brilliantly ambiguous headline on Helge Lund’s forced departure encapsulates this.

To state the obvious, these different types of investors use different tools and work to different timescales. The use of derivatives by activists of the Elliott type is commonplace, whereas I’m guessing all those investors that voted against Lund last week would be traditional equity investors. The latter group were focused on the AGM, as a normal ‘set piece’ when escalating engagement, whereas Elliott seems to have been largely uninterested.

And, as I’ve noted many times before, Elliott doesn’t pretend to adhere to the Stewardship Code, despite the significant influence it seeks to have on UK PLCs like BP. (But then derivatives don’t even get a mention in the Code.)

In practice that means only one of these two models is required to produce voluminous reporting on how it approaches engagement with companies, which in turn is assessed by a regulator to see if it’s good enough. And only one model shells out to acquire an actual shareholding in companies which underpins engagement. It does feel like a rather unequal set-up.

Most importantly, which of these models do you think is likely to have the greater influence on BP’s strategy? And if ‘stewardship’ is to be assessed primarily on outcomes, rather than policies and intentions, should Elliott claim the mantle even if many don’t share its objectives?